| |

Bipolar disorder, also known as bipolar affective

disorder, manic-depressive disorder, or manic

depression, is a mental illness classified by

psychiatry as a mood disorder. Individuals with

bipolar disorder experience episodes of an elevated

or agitated mood known as mania alternating with

episodes of depression.

Those with bipolar disorder often describe their

experience as being on an emotional roller coaster.

Cycling up and down between strong emotions can keep

a person from having anything approaching a “normal”

life. The emotions, thoughts and behavior of a

person with bipolar disorder are often experienced

as beyond one’s control. Friends, co-workers and

family may sometimes intervene to try and help

protect their interests and health. This makes the

condition exhausting not only for the sufferer, but

for those in contact with her or him as well.

About 4% of people suffer from bipolar disorder.

Prevalence is similar in men and women and, broadly,

across different cultures and ethnic groups

In bipolar disorder, people experience abnormally

elevated (manic or hypomanic) mood states which

interfere with the functions of ordinary life. Many

people with bipolar disorder also experience periods

of depressed mood, but this is not universal. There

is no simple physiological test to confirm the

disorder. Diagnosing bipolar disorder is often

difficult, even for mental health professionals

Mania is the defining feature of bipolar disorder.

Mania is a distinct period of elevated or irritable

mood, which can take the form of euphoria, and lasts

for at least a week (less if hospitalization is

required). People with mania commonly experience an

increase in energy and a decreased need for sleep,

with many often getting as little as three or four

hours of sleep per night. Some can go days without

sleeping. A manic person may exhibit pressured

speech, with thoughts experienced as racing.

Attention span is low, and a person in a manic state

may be easily distracted. Judgment may be impaired,

and sufferers may go on spending sprees or engage in

risky behavior that is not normal for them. They may

indulge in substance abuse, particularly alcohol or

other depressants, cocaine or other stimulants, or

sleeping pills. Their behavior may become

aggressive, intolerant, or intrusive. They may feel

out of control or unstoppable, or as if they have

been "chosen" and are "on a special mission", or

have other grandiose or delusional ideas. Sexual

drive may increase. At more extreme levels, a person

in a manic state can experience psychosis or a break

with reality, where thinking is affected along with

mood. This can occasionally lead to violent

behaviors. The severity of manic symptoms can be

measured by rating scales such as the Altman

Self-Rating Mania Scale and clinician-based Young

Mania Rating Scale.

Hypomania is a mild to moderate level of elevated

mood, characterized by optimism, pressure of speech

and activity, and decreased need for sleep.

Generally, hypomania does not inhibit functioning as

mania does. Many people with hypomania are actually

more productive than usual, while manic individuals

have difficulty completing tasks due to a shortened

attention span. Some hypomanic people show increased

creativity, although others demonstrate poor

judgment and irritability. Many experience hyper

sexuality. Hypomanic people generally have increased

energy and increased activity levels. They do not,

however, have delusions or hallucinations.

Hypomania may feel good to the person who

experiences it. Thus, even when family and friends

recognize mood swings, the individual often will

deny that anything is wrong. What might be called a

"hypomanic event", if not accompanied by depressive

episodes, is often not deemed as problematic, unless

the mood changes are uncontrollable, volatile or

mercurial. If left untreated, an episode of

hypomania can last anywhere from a few days to

several years. Most commonly, symptoms continue for

a few weeks to a few months.

Signs and symptoms of the depressive phase of

bipolar disorder include persistent feelings of

sadness, anxiety, guilt, anger, isolation, or

hopelessness; disturbances in sleep and appetite;

fatigue and loss of interest in usually enjoyable

activities; problems concentrating; loneliness,

self-loathing, apathy or indifference;

depersonalization; loss of interest in sexual

activity; shyness or social anxiety; irritability,

chronic pain (with or without a known cause); lack

of motivation; and morbid suicidal thoughts. In

severe cases, the individual may become psychotic, a

condition also known as severe bipolar depression

with psychotic features. These symptoms include

delusions or, less commonly, hallucinations, usually

unpleasant. A major depressive episode persists for

at least two weeks, and may continue for over six

months if left untreated.

A mixed state, also known as dysphoric mania,

agitated depression, or a mixed episode, is a

condition during which features of mania and

depression, such as agitation, anxiety, fatigue,

guilt, impulsiveness, irritability, morbid or

suicidal ideation, panic, paranoia, pressured speech

and rage, occur simultaneously.

Typical examples include tearfulness during a manic

episode or racing thoughts during a depressive

episode. One may also feel incredibly frustrated or

be prone to fits of rage in this state, since one

may feel like a failure and at the same time have a

flight of ideas. Mixed states are often the most

problematic period of mood disorders, during which

susceptibility to substance abuse, panic disorder,

commission of violence, suicide attempts, and other

complications increase greatly.

A mixed state must meet the criteria for a major

depressive episode and a manic episode nearly every

day for at least one week. However, mixed episodes

rarely conform to these qualifications; they may be

described more practically as any combination of

depressive and manic symptoms.

Bipolar I disorder (pronounced "bipolar one" and

also known as manic-depressive disorder or manic

depression) is a form of mental illness. A person

affected by bipolar I disorder has had at least one

manic episode in his or her life.Most people are in

their teens or early 20s when symptoms of bipolar

disorder first appear. Nearly everyone with bipolar

I disorder develops it before age 50. People with an

immediate family member who has bipolar are at

higher risk.Many people with bipolar I disorder

experience long periods without symptoms in between

episodes. A minority has rapid-cycling symptoms of

mania and depression, in which they may have

distinct periods of mania or depression four or more

times within a year. People can also have mixed

episodes, in which manic and depressive symptoms

occur simultaneously, or may alternate from one pole

to the other within the same day.

A. Presence of only one Manic Episode and no past

Major Depressive Episodes.

Note: Recurrence is defined as either a change in

polarity from depression or an interval of at least

2 months without manic symptoms.

B. The Manic Episode is not better accounted for by

Schizoaffective Disorder and is not superimposed on

Schizophrenia, Schizophreniform Disorder, Delusional

Disorder, or Psychotic Disorder Not Otherwise

Specified.

DSM-IV- TRCriteria for Bipolar I Disorder, Most

Recent Episode Hypomanic

A. Currently (or most recently) in a Hypomanic

Episode.

B. There has previously been at least one Manic

Episode or Mixed Episode.

C. The mood symptoms cause clinically significant

distress or impairment in social, occupational, or

other important areas of functioning.

D. The mood episodes in Criteria A and B are not

better accounted for by Schizoaffective Disorder and

are not superimposed on Schizophrenia,

Schizophreniform Disorder, Delusional Disorder, or

Psychotic Disorder Not Otherwise Specified.

A. Currently (or most recently) in a Manic Episode.

B. There has previously been at least one Major

Depressive Episode, Manic Episode, or Mixed Episode.

C. The mood episodes in Criteria A and B are not

better accounted for by Schizoaffective Disorder and

are not superimposed on Schizophrenia,

Schizophreniform Disorder, Delusional Disorder, or

Psychotic Disorder Not Otherwise Specified.

DSM-IV-TRCriteria for Bipolar I Disorder, Most

Recent Episode Mixed

A. Currently (or most recently) in a Mixed Episode.

B. There has previously been at least one Major

Depressive Episode, Manic Episode, or Mixed Episode.

C. The mood episodes in Criteria A and B are not

better accounted for by Schizoaffective Disorder and

are not superimposed on Schizophrenia,

Schizophreniform Disorder, Delusional Disorder, or

Psychotic Disorder Not Otherwise Specified.

A. Currently (or most recently) in a Major

Depressive Episode.

B. There has previously been at least one Manic

Episode or Mixed Episode.

C. The mood episodes in Criteria A and B are not

better accounted for by Schizoaffective Disorder and

are not superimposed on Schizophrenia,

Schizophreniform Disorder, Delusional Disorder, or

Psychotic Disorder Not Otherwise Specified.

A. Criteria, except for duration, are currently (or

most recently) met for a Manic, a Hypomanic, a

Mixed, or a Major Depressive Episode.

B. There has previously been at least one Manic

Episode or Mixed Episode.

C. The mood symptoms cause clinically significant

distress or impairment in social, occupational, or

other important areas of functioning.

D. The mood episodes in Criteria A and B are not

better accounted for by Schizoaffective Disorder and

are not superimposed on Schizophrenia,

Schizophreniform Disorder, Delusional Disorder, or

Psychotic Disorder Not Otherwise Specified.

E. The mood symptoms in Criteria A and B are not due

to the direct physiological effects of a substance

(e.g., a drug of abuse, a medication, or other

treatment) or a general medical condition (e.g.,

hyperthyroidism).

Bipolar II disorder is a bipolar spectrum disorder

characterized by at least one episode of hypomania

and at least one episode of major depression.

Diagnosis for bipolar II disorder requires that the

individual must never have experienced a full manic

episode (one manic episode meets the criteria for

bipolar I disorder. The course of bipolar II

disorder is more chronic and consists of more

frequent cycling than the course of bipolar I

disorder. Bipolar II is associated with a greater

risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviors than bipolar

I or unipolar depression. Although bipolar II is

commonly perceived to be a milder form of Type I,

this is not the case. Types I and II present equally

severe burdens. Bipolar II is difficult to diagnose.

Patients usually seek help when they are in a

depressed state. Because the symptoms of hypomania

are often mistaken for high functioning behavior or

simply attributed to personality, patients are

typically not aware of their hippomanic symptoms.

As a result, they are unable to provide their doctor

with all the information needed for an accurate

assessment; these individuals are often misdiagnosed

with unipolar depression. Of all individuals

initially diagnosed with major depressive disorder,

between 40% and 50% will later be diagnosed with

either BP-I or BP-II. Despite the difficulties, it

is important that BP-II individuals are correctly

assessed so that they can receive the proper

treatment.

A. Presence (or history) of one or more Major

Depressive Episodes.

B. Presence (or history) of at least one Hypomanic

Episode.

C. There has never been a Manic Episode or a Mixed

Episode.

D. The mood symptoms cause clinically significant

distress or impairment in social, occupational, or

other important areas of functioning.

E. The mood episodes in Criteria A and B are not

better accounted for by Schizoaffective Disorder and

are not superimposed on Schizophrenia,

Schizophreniform Disorder, Delusional Disorder, or

Psychotic Disorder Not Otherwise Specified.

F. The symptoms cause clinically significant

distress or impairment in social, occupational, or

other important areas of functioning.

Cyclothymia or cyclothymic disorder is a relatively

mild mood disorder. In cyclothymic disorder, moods

swing between short periods of mild depression and

hypomania, an elevated mood. The low and high mood

swings never reach the severity of major depression

or mania.In cyclothymia, moods fluctuate from mild

depression to hypomania and back again. In most

people, the pattern is irregular and unpredictable.

Hypomania or depression can last for days or weeks.

In between up and down moods, a person might have

normal moods for more than a month -- or may cycle

continuously from hypomanic to depressed, with no

normal period in between.

A. For at least 2 years, the presence of numerous

periods with hypomanic symptoms (see p. 338) and

numerous periods with depressive symptoms that do

not meet criteria for a Major Depressive Episode.

Note: In children and adolescents, the duration must

be at least 1 year.

B. During the above 2-year period (1 year in

children and adolescents), the person has not been

without the symptoms in Criterion A for more than 2

months at a time.

C. No Major Depressive Episode, Manic Episode, or

Mixed Episode has been present during the first 2

years of the disturbance.

Note: After the initial 2 years (1 year in children

and adolescents) of Cyclothymic Disorder, there may

be superimposed Manic or Mixed Episodes (in which

case both Bipolar I Disorder and Cyclothymic

Disorder may be diagnosed) or Major Depressive

Episodes (in which case both Bipolar II Disorder and

Cyclothymic Disorder may be diagnosed).

D. The symptoms in Criterion A are not better

accounted for by Schizoaffective Disorder and are

not superimposed on Schizophrenia, Schizophreniform

Disorder, Delusional Disorder, or Psychotic Disorder

Not Otherwise Specified.

E. The symptoms are not due to the direct

physiological effects of a substance (e.g., a drug

of abuse, a medication) or a general medical

condition (e.g., hyperthyroidism).

F. The symptoms cause clinically significant

distress or impairment in social, occupational, or

other important areas of functioning.

The current thinking is that this is a predominantly

biological disorder that occurs in a specific part

of the brain and is due to a malfunction of the

neurotransmitters (chemical messengers in the

brain). As a biological disorder, it may lie dormant

and be activated spontaneously or it may be

triggered by stressors in life.

Although, no one is quite sure about the exact

causes of bipolar disorder, researchers have found

these important clues:

• Bipolar disorder tends to be familial, meaning

that it “runs in families.” About half the people

with bipolar disorder have a family member with a

mood disorder, such as depression.

• A person who has one parent with bipolar disorder

has a 15 to 25 percent chance of having the

condition.

• A person who has a non-identical twin with the

illness has a 25 percent chance of illness, the same

risk as if both parents have bipolar disorder.

• A person who has an identical twin (having exactly

the same genetic material) with bipolar disorder has

an even greater risk of developing the illness about

an eightfold greater risk than a nonidentical twin.

• Studies of adopted twins (where a child whose

biological parent had the illness is raised in an

adoptive family untouched by the illness) has helped

researchers learn more about the genetic causes vs.

environmental and life events causes.

Environmental Factors in Bipolar Disorder:

• A life event may trigger a mood episode in a

person with a genetic disposition for bipolar

disorder.

• Even without clear genetic factors, altered health

habits, alcohol or drug abuse or hormonal problems

can trigger an episode.

• Among those at risk for the illness, bipolar

disorder is appearing at increasingly early ages.

This apparent increase in earlier occurrences may be

due to underdiagnosis of the disorder in the past.

This change in the age of onset may be a result of

social and environmental factors that are not yet

understood.

Although the abnormalities in the brain due to

bipolar disorder are still unknown, the structural

abnormalities believed to be linked to bipolar

disorder are amygdala, basal ganglia, and the

prefrontal cortex. Research is currently being

conducted to find more definite information on the

definite causes and changes in the brain of bipolar

disorder.

Recently using MRI, hyperintense (bright white)

spots have been found in bipolar patients.

Hyperintensities have previously been associated

with a change in water content in the brain tissue,

but the causes of these are not known.

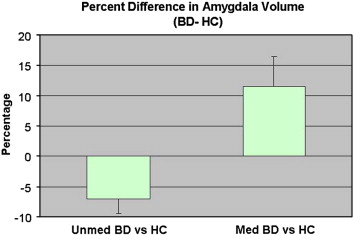

Amygdala volumes have been shown to be reduced in

unmediated patients and increased in medicated

patients. This is seen in the chart below.

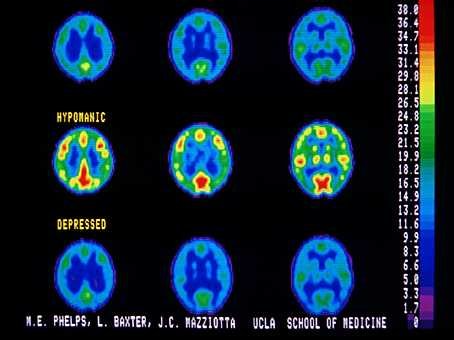

In this figure, normal brain scans are at the top,

hypomanic is in the middle row and depressed are at

the bottom. You can see the reduced activity in the

depressed brain, by the presence of more dark blue

and can see the over activity in the manic brain by

the presence of more green, yellow and red in the

brain scan.

BD patients and healthy control subjects

Abnormalities in the structure and/or function of

certain brain circuits could underlie bipolar.

Meta-analyses of structural MRI studies in bipolar

disorder report an increase in the volume of the

lateral ventricles, globuspallidus and increase in

the rates of deep white matter hyper intensities.

Functional MRI findings suggest that abnormal

modulation between ventral prefrontal and limbic

regions, especially the amygdale, likely contribute

to poor emotional regulation and mood symptoms.

Medication is a necessary part of treatment for

bipolar disorder but psychological treatment can

supplement medication.

Psychoeducational approaches typically help people

learn about the symptoms of the disorder, the

expected time course of symptoms, the biological and

psychological triggers for symptoms and treatment

strategies. Studies confirm that careful education

about bipolar disorder can help people adhere to

treatment with medications such as lithium.

Family focused treatment (FFT) aims to educate the

family about the illness, enhance family

communication and develop problem solving skills.

FFT leads to lower rates of relapse when added to

medication.

Lithium (brand names Eskalith, Lithobid) is the most

widely used and studied medication for treating

bipolar disorder. Lithium helps reduce the severity

and frequency of mania. It may also help relieve

bipolar depression.

Studies show that lithium can significantly reduce

suicide risk. Lithium also helps prevent future

manic and depressive episodes. As a result, it may

be prescribed for long periods of time (even between

episodes) as maintenance therapy.

Lithium acts on a person's central nervous system

(brain and spinal cord). It is thought to help

strengthen nerve cell connections in brain regions

that are involved in regulating mood, thinking and

behavior.

The dose of lithium varies among individuals and as

phases of their illness change. Although bipolar

disorder is often treated with more than one drug,

some people can control their condition with lithium

alone.

Benzodiazepines rapidly help control certain manic

symptoms in bipolar disorder until mood-stabilizing

drugs can take effect. They are usually taken for a

brief time, up to two weeks or so, with other

mood-stabilizing drugs. They may also help restore

normal sleep patterns in people with bipolar

disorder.

Benzodiazepines slow the activity of the brain. In

doing so, they can help treat mania, anxiety, panic

disorder, insomnia, and seizures.

Benzodiazepines prescribed for bipolar disorder

include (among others):

Ativan (lorazepam)

Klonopin (clonazepam)

Valium (diazepam)

Xanax (alprazolam)

Electroconvulsive therapy, also known as ECT or

electroshock therapy, is a short-term treatment for

severe manic or depressive episodes, particularly

when symptoms involve serious suicidal or psychotic

symptoms, or when medicines seem to be ineffective.

It can be effective in nearly 75% of patients.

For many individuals with bipolar disorder a good

prognosis results from good treatment, which, in

turn, results from an accurate diagnosis. Because

bipolar disorder can have a high rate of both

under-diagnosis and misdiagnosis, it is often

difficult for individuals with the condition to

receive timely and competent treatment.

Bipolar disorder can be a severely disabling medical

condition. However, many individuals with bipolar

disorder can live full and satisfying lives. Quite

often, medication is needed to enable this. Persons

with bipolar disorder may have periods of normal or

near normal functioning between episodes.

|

|